Jennifer Higdon:

Machine

Jennifer Higdon was born in Brooklyn, NY on December 31, 1962. She is one of America’s most acclaimed and most frequently performed living composers. She has become a major figure in contemporary Classical music, receiving the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Violin Concerto, a 2010 GRAMMY for her Percussion Concerto and a 2018 GRAMMY for her Viola Concerto. Higdon enjoys several hundred performances a year of her works, and blue cathedral is one of today’s most performed contemporary orchestral works, with more than 500 performances worldwide. Her works have been recorded on more than sixty CDs. Higdon’s first opera, Cold Mountain, won the prestigious International Opera Award for Best World Premiere and the opera recording was nominated for 2 GRAMMY awards. Dr. Higdon now holds the Rock Chair in Composition at The Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Her music is published exclusively by Lawdon Press. Machine lasts a mere two minutes and was commissioned as an encore piece in 2003 by the National Symphony Orchestra through a grant from the John and June Hechinger Commissioning Fund for New Orchestra Works. It was first performed by the National Symphony Orchestra under the conductor Giancarlo Guerrero on March 6, 2003. The work is scored for piccolo, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Jennifer Higdon provides the following pithy program notes for Machine:

I wrote “Machine” as an encore tribute to composers like Mozart and Tchaikovsky, who seemed to be able to write so many notes and so much music that it seems like they were machines! This work was commissioned in 2003 by The National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C., Leonard Slatkin, Music Director, through a grant from The John and June Hechinger Commissioning Fund for New Orchestra Works. The premiere was given by The National Symphony Orchestra, Giancarlo Guerrero, conducting.

According to a review in the Washington Post, music critic Ronald Broun wrote, “It is one long, loud, freight-train crescendo with hellishly snapping winds and jumping-bean rhythms, and it sweeps relentlessly forward for just under three minutes, then stops on a dime. For sheer unpretentious fun it was just the ticket.”

Program Note by David B. Levy/Jennifer Higdon, © 2018

Missy Mazzoli:

These Worlds In Us

American composer and pianist, Missy Mazzoli, was born in Lansdale, PA on October 27, 1980. She studied at the Yale School of Music, the Royal Conservatory of the Hague and Boston University. Her teachers have been David Lang, Louis Andriessen, Aaron Jay Kernis, Martin Bresnick, Martijn Padding, and John Harbison. Having previously taught at Yale, she is now a member of the composition faculty at the Mannes College of Music. Mazzoli has received critical acclaim for her chamber, orchestral and operatic work. She is also the founder and keyboardist for Victoire, an electro-acoustic band dedicated to performing her music. Her music is published by G. Schirmer. These Worlds in Us is a nine-minute piece for orchestra composed in 2006. Winner of the 2007 ASCAP Young Composers Award and the Woods Chandler Prize for best orchestral composition for the Yale Philharmonia, it was first performed on March 1, 2006 by the Yale Philharmonia and received its first professional performance on December 1, 2006 by the Minnesota Orchestra, conducted by Osmo Vänskä. The work is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, percussion, 2 melodicas (or synths), and strings.

The following program note was written by the composer:

The title These Worlds In Us comes from James Tate’s poem The Lost Pilot, a meditation on his father’s death in World War II:

(excerpt)

My head cocked towards the sky,

I cannot get off the ground,

and you, passing over again,fast, perfect and unwilling

to tell me that you are doing

well, or that it was a mistakethat placed you in that world,

and me in this; or that misfortune

placed these worlds in us.This piece is dedicated to my father, who was a soldier during the Vietnam War. In talking to him it occurred to me that, as we grow older, we accumulate worlds of intense memory within us, and that grief is often not far from joy. I like the idea that music can reflect painful and blissful sentiments in a single note or gesture, and sought to create a sound palette that I hope is at once completely new and strangely familiar to the listener. The theme of this work, a mournful line first played by the violins, collapses into glissandos almost immediately after it appears, giving the impression that the piece has been submerged under water or played on a turntable that is grinding to a halt. The melodicas (mouth organs) played by the percussionists in the opening and final gestures mimic the wheeze of a broken accordion, lending a particular vulnerability to the bookends of the work. The rhythmic structures and cyclical nature of the piece are inspired by the unique tension and logic of Balinese music, and the march-like figures in the percussion bring to mind the militaristic inspiration for the work as well as the relentless energy of electronica drum beats.

(http://www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/work/45740)

Program Note by David B. Levy/Missy Mazzoli, © 2018

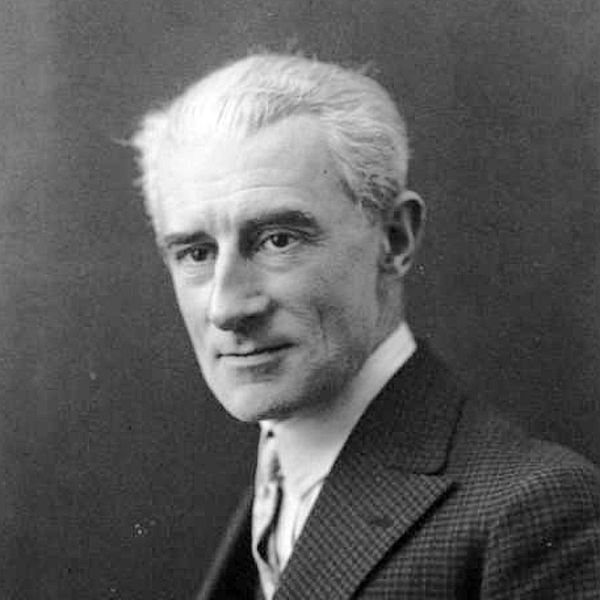

Maurice Ravel

Piano Concerto in G Major

Maurice Ravel was born March 7, 1875 of parents of Swiss and Basque descent in Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées. He died December 28, 1937 in Paris. His Piano Concerto in G Major was composed between 1929 and 1931 and Marguerite Long gave the work its premiere performance in Paris on January 14, 1932. It is scored for piccolo, flute, oboe, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, harp, percussion, and strings.

After Ravel’s highly successful tour of the United States in 1928, hopes for a second one followed. The Boston Symphony Orchestra commissioned Ravel to provide a concerto for piano and orchestra for its fiftieth anniversary, with the expectation that the composer would also serve as a soloist. The composer began work on this piece in 1929. He continued the process through 1931, working simultaneously on the Concerto for the Left Hand for Paul Wittgenstein. Ravel considered this double assignment to be an “interesting experiment.” To his credit, he succeeded in inventing two distinctly individual compositions, despite the danger of confusing the two projects.

Ravel completed the Wittgenstein piece in August of 1930. Fatigued by the effort, Ravel communicated to a friend his concern that work on the two pieces was causing him considerable tension. He subsequently abandoned the idea of performing the Piano Concerto in G Major himself, and he passed that honor instead to the work’s dedicatee, Marguerite Long. Ravel did eventually play the work later in Europe, but never in the United States as originally planned.

Ravel remarked that the Piano Concerto in G Major was conceived in the spirit of Mozart and Camille Saint-Saëns. Indeed, the five concertos by the latter represented the finest achievements in this genre by any French composer before this time. The Mozartian inspiration may be discerned in Ravel’s Adagio assai, whose music evokes the slow movement of Mozart’s Quintet for Clarinet and Strings. Further influencesmdash;most notably those of Stravinsky and of jazzmdash;figure prominently in the piece whose effervescence derives from a piquant harmonic language, brilliant orchestration, and virtuosic passagework for the soloist.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2002/2018

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op.74

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on May 7, 1840 in Votinsk, Russia and died on November 6, 1893 in Saint Petersburg. He remains one of the most popular composers of all time, beloved especially for his symphonies, ballets, and concertos. His Symphony no. 6 was composed between February and August 1893, the final year of his life, and received its first performance in St. Petersburg on 28 October of that year. It is scored for piccolo, 3 flutes (third doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, and strings.

The composer’s brother, Modest, suggested that Tchaikovsky’s be labeled “Tragic,” but this name was rejected and the composer agreed to its popular title of “Pathétique.” Consideration of title aside, the Symphony no. 6 is the crowning achievement of one of the most effective symphonists who ever lived. The circumstances surrounding the composer’s death—was it suicide prompted by the revelation of his homosexual liaison, or did he die of poisoning from drinking a glass of unboiled water?—only adds to the mystique surrounding this, the most unorthodox of all his symphonies. Scholars still disagree as to the truth of the matter, but when asked if the “Pathétique” had a program, Tchaikovsky responded only by confessing that it “is saturated with subjective feeling” and that “in my mind I shed many tears [in composing it].” Nothing conclusive here.

For those who turn to biographical events to explain how a certain piece of music came into existence and to gain understanding of the nature of that piece ought to bear in mind that Tchaikovsky penned one of his most cheerful scores, “The Nutcracker” ballet, at the same time he was working on the Symphony no. 6, his most fatalistic composition. Donald Francis Tovey has said of the “Pathétique” Symphony: “All Tchaikovsky’s music is dramatic; and the Pathetic Symphony is the most dramatic of all his works. Little or nothing is to be gained by investigating it from a biographical point of view . . .” With this in mind, one must turn to the work itself to learn what makes it such a special part of the orchestral repertory.

There can be no disagreement as to this symphony’s inherent dramatic qualities, which are most abundantly apparent in its outer movements. Only a composer confident in his abilities as a dramatist would dare to end a symphony with the desperate Adagio lamentoso, with pulsating cellos and basses fading to pppp, an extraordinary fading away to the softest dynamic level possible. A primary factor that endears Tchaikovsky’s music to so many listeners is a wealth of tuneful melodies. What can rival the beauty and lyricism of the famous second theme of the first movement or the felicitous tune of the 5/4 meter Allegro con grazia second movement? Another salient feature of Tchaikovsky’s style is its mastery of orchestration. Here too, the “Pathétique” Symphony will not be found wanting. Among the most ingenious moments may be found in the sonorities that he invokes at the end of the first movement (pizzicato strings in descending scales as a background to the singing winds and brass), the brilliant opulence of the Allegro molto vivace scherzo, and the dark and brooding tension of the finale. The descending scale, in fact, is a feature that may be found toward the end of each of the symphony’s four movements, a feature that unites its disparate parts.

The sum of the parts, however, add up to something less than the whole of this masterpiece of orchestral music. Its drama speaks eloquently for itself, and the impression that it makes defies analytical explanation. One must, in the final analysis, sense the spirit of the “Pathétique” Symphony as the work of profound expression that it is.

Program note by David B. Levy © 2000/2017