Franz Schubert

Symphony no. 4 in C Minor, D. 417 (“Tragic”)

Franz Peter Schubert was born in Vienna on January 21, 1797 and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed a wide variety of music, but his most enduring contributions were to the repertory of song for voice and piano. As best as can be determined, Schubert composed over six hundred accompanied songs in his brief life, as well as a large number of solo piano compositions, operas, sacred vocal works, and chamber music. His gift as a lyrical composer may also be heard in his purely instrumental music. His Symphony no. 4 was composed in 1816 when the composer was only nineteen years old. For unknown reasons he later added the title, “Tragic,” perhaps to render it more marketable. It was not performed in public until November 19, 1849 in Leipzig. The work is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

The history of symphonic music might have changed significantly had Franz Schubert’s contributions to the genre stood in the foreground of his Vienna. The dominant figure of his time, of course, was none other than Ludwig van Beethoven, who, by the time Schubert composed his Symphony no. 4, had already composed eight of his nine monumental symphonies. Schubert’s lyrical gift and harmonic ingenuity in some respects outstripped that of the elder master, to whom he looked up and without whose influence, Schubert could not entirely escape. One additional interesting aspect of this symphony is that it was not published until 1884, and at that edited by none other than Johannes Brahms, who may have inserted some of his own emendations. Only since 1965 are we seeing new critical editions of Schubert’s works that come closer to the original conception of this and other compositions. A new critical edition of Symphony no. 4 was issued in 1999.

In any event, symphonic music in early 19th-century Vienna took a back seat to other genres, most notably opera. There was not even an established orchestra that existed for the sole purpose of performing concert pieces for orchestra. Public performances of symphonies relied on the composer being able to marshal the personnel from opera orchestras and securing a suitable venue. There was no Musikverein (built in 1870) and no Vienna Philharmonic (established in 1847). Symphonies, therefore, were often performed in smaller venues for private audiences and such was the case with most of those composed by Schubert. It was characteristic of this composer, who most of his short life shunned the public spotlight, to play down his achievements as a composer of symphonies. Time has proven that even his earliest efforts are meritorious beyond his self-assessment.

The first movement of Schubert’s Fourth Symphony begins with a dramatic introduction (Adagio molto) which could have been inspired by the “Depiction of Chaos” opening of Joseph Haydn’s oratorio, The Creation, but which also carries traces of the influence of Christoph Willibald Glück. The ensuing Allegro vivace shows the possible influence of the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet, Op. 18, no. 4—a work in the same key of C Minor with which Schubert surely could have been familiar (Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata, also in C Minor, cannot be eliminated as another possible inspiration). Unlike Beethoven’s penchant for ending the movement in a minor key, Schubert elects, Haydn-like, to allow the brighter major mode hold sway.

If any movement hints at the possibility of the influence of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5, it could be the gently lyrical Andante in A-flat Major second movement. This rondo on occasion attempts to equal Beethoven’s boldness, especially in its second and fourth sections, but falls back mainly on its more serene tunefulness. The third movement is labeled Menuetto. Allegro vivace and is notable for several reasons. As is the case with Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1, the title, “Menuetto” is deceptive, as it is in fact closer to the spirit of a scherzo than a courtly dance. Another unusual feature is Schubert’s choice of tonality: E-flat Major. Normally the third movement of a symphony would return to the home key of the first movement—in this case C Minor. Finally, the movement’s high level of chromaticism and brief excursions into foreign keys show an adventurous nature of Schubert’s harmonic muse. The energetic final movement, Allegro, brings us back home to C Minor as well as the piquant chromatic inflections that are a hallmark of the first and third movements. The symphony ends optimistically in C Major, but not without the signature chromaticism that permeates so much of the work.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2018

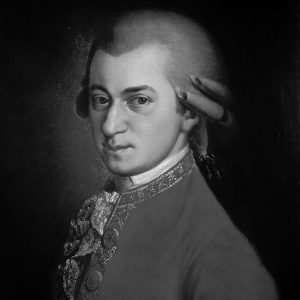

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Requiem in D minor, K. 626 // Robert Levin edition

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg. He died on December 5, 1791 in Vienna. The Requiem in D Minor, K. 626, was composed, but remained unfinished at the composer’s death in 1791. The autograph ends after the first eight measures of the “Lacrimosa” movement. Some sketched ideas for other movements were left behind and the first attempt at completing the work was made by Mozart’s assistant, Franz Xaver Süssmayr The “K” number used for Mozart’s works refers to the name Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, who first issued the Chronological-Thematic Catalogue of the Complete Works of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in 1862. The Köchel catalogue has been updated and revised several times. The work is scored for four-voice mixed choir, four solo voices 2 clarinets (basset horns), 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings, and organ.

An air of mystery and no small amount of controversy has always surrounded Mozart’s Requiem. This should not be totally unexpected when a major composer leaves behind the torso of an important composition. The fact that the composer in question died prematurely while still at work on the composition of a Mass for the Dead, only increases the sense of intrigue. Popular culture’s portraiture of Mozart, abetted in recent years by Peter Shaeffer’s play and film, Amadeus, has served only to confuse the issue further.

The facts of the matter are as follows: Mozart received a commission to compose a Requiem Mass in the summer of 1791 from Count Franz von Walsegg, who wished to memorialize his wife, Anna, who died in February of that year. The unscrupulous Walsegg, however, concealed his identity from Mozart because he planned, as he had done before, to copy the score and pass it off as a work of his own. Mozart was paid an advance of half his commission upon his acceptance of the project, and he was to have received the balance upon its completion. But other projects, La Clemenza di Tito, The Magic Flute, and a cantata for the Masonic lodge to which he belonged, postponed work on the Requiem. By the time he got to work on it in late November, Mozart’s final illness began to overtake him. The composer thought that he had been poisoned, and he frantically worked on the Requiem, now believing that it would be for himself. Mozart managed to complete to the first movement (Introit and Kyrie) before his death, and left behind the voice parts, bass line, and certain instrumental parts through measure eight of the Lacrimosa. He had also completed some work on the Domine Jesu Christe and Hostias.

Upon Mozart’s death, his widow, Constanze, set about to find someone who could complete the Requiem, and thus gain for her and her two children, the balance of Walsegg’s (whose identity still was unknown to her) lucrative commission. The first composer to work on it was Joseph Eybler, who worked on the orchestration, but soon abandoned the project. Constanze next turned to a former pupil of her husband’s, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who “completed” the work in February of 1792. She sold a copy of the score to King Wilhelm III of Prussia, and the Baron Gottfried van Swieten, an important figure in Viennese musical life and an acquaintance of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, arranged for the Requiem to be performed on January 2, 1793. Walsegg performed it later that year from a copy of the score that attributed the Requiem to himself.

Süssmayr was among the first people to acknowledge the inadequacy of his “completion” of Mozart’s Requiem. Many subsequent editors and composers have offered alternative versions. Musicologist and pianist Robert D. Levin, a member the music faculty of Harvard University, has prepared the version heard in this performance directed by Christopher Gilliam. It is a highly appealing and well-reasoned edition that has received frequent performances and been recorded (Telarc CD-80410). Here is a portion of Levin’s commentary from the liner notes accompanying this recording:

The version heard on this recording seeks to address the problems of instrumentation, grammar, and structure within Süssmayr’s version while respecting the [more than] 200-year-old history of the Requiem. A clearly drawn line of separation, in which everything except the contents of Mozart’s autograph was to be considered spurious per se, was explicitly rejected. Rather, the goal was to revise not as much, but as little as possible, attempting in the revisions to observe the character, texture, voice leading, continuity, and structure of Mozart’s music. The traditional version has been retained insofar as it agrees with idiomatic Mozartean practice. The more transparent instrumentation of the new completion was inspired by Mozart’s other church music. The Lacrimosa has been slightly altered and now leads into a non-modulating Amen fugue. (Other completions of the fugue modulate extensively.) The second half of the Sanctus resolves the curious tonal discrepancies of Süssmayr’s version, and the revised Hosanna fugue, modeled after that of Mozart’s C-minor Mass K. 427/417a, displays the proportions of a Mozartean church fugue. The second half of the Benedictus has been slightly revised and is connected by a new transition to a shortened reprise of the Hosanna fugue in the original key of D major. The structure of Agnus Dei has been retained, but the infelicities of Süssmayr’s version have been averted in the second and third strophes. In the final Cum sanctis tuis fugue, the text setting has been altered to correspond to the norms of the era. It is hoped that the new version honors Mozart’s spirit while allowing the listener to experience Mozart’s magnificent Requiem torso within the sonic framework of its historical tradition.

Program Note by David B. Levy, ©1997/2018