Witold Lutosławski: Concerto for Orchestra

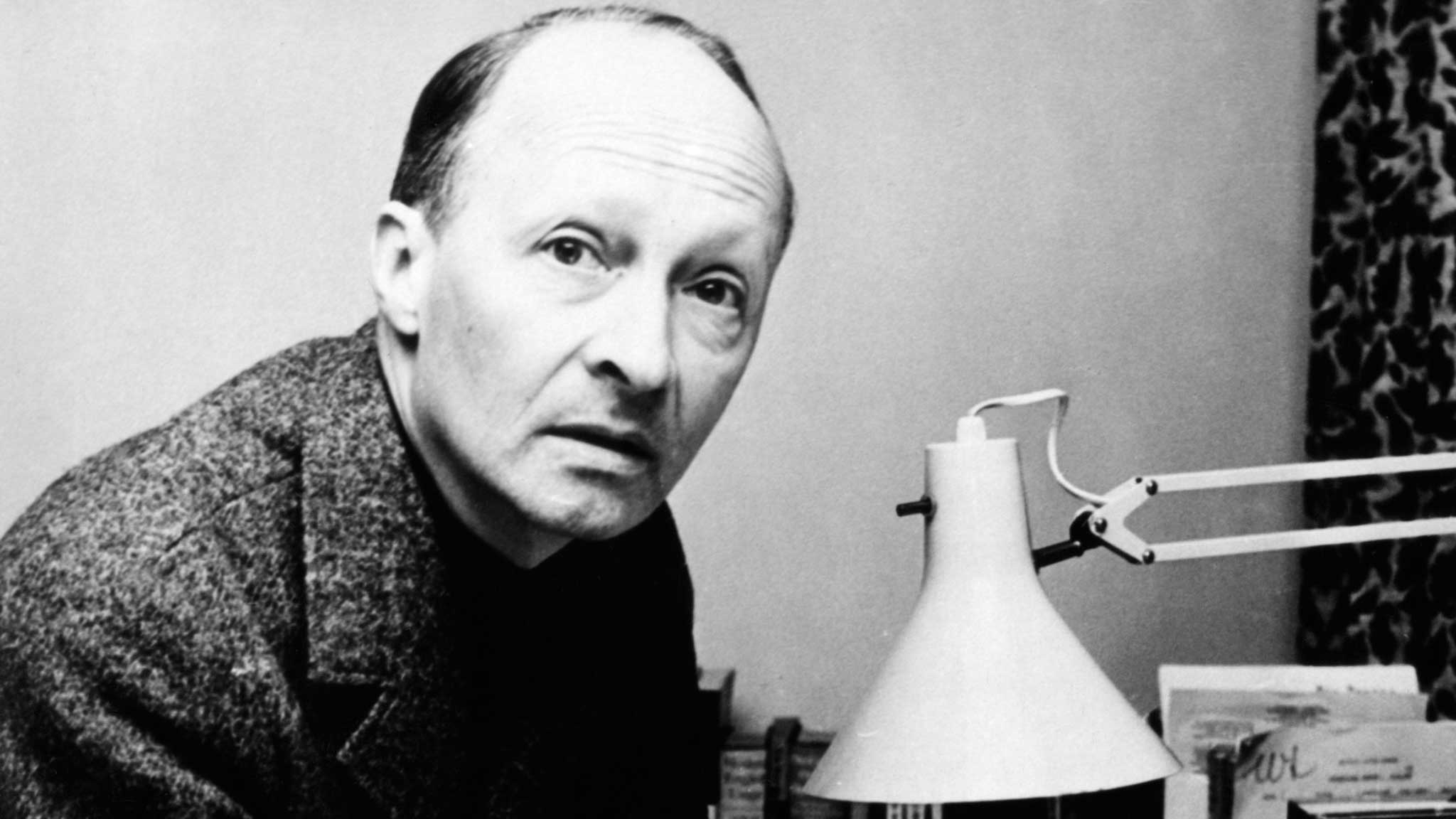

Polish composer Witold Lutosławski was born in Warsaw on January 25, 1913 and died there on February 9, 1994. He was the youngest son of the amateur pianist, Józef Lutosławski (1881–1918). Józef and his family were caught between those in Poland who sought to align with German expansionists and those who sought to associate with Russia, which at the time of Witold’s birth stood on the precipice of the First World War, and his family had yet to experience effects of the coming Russian Revolution of 1917.

Its premiere took place in Prague on OcIn the year of Witold’s birth, Warsaw was part of the Vistulaland province of Imperial Russia. The family’s move to Moscow proved to be a fatal one for Józef, as the forces of the Bolsheviks led to his execution. After his mother moved the family to Ukraine, they returned to what was now Poland at the end of 1918. The Concerto for Orchestra was composed between 1950 and 1954 at the suggestion of Witold Rowicki, the artistic director of the Warsaw Philharmonic, who was the recipient of the work’s dedication. Its first performance took place on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw with Rowicki conducting the Warsaw National Symphony Orchestra. The large scoring calls for 3 flutes (2 doubling piccolo, 3 oboes (third doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, celesta, 2 harps, piano, and strings.tober 14, 1883 with František Ondřĭček as soloist and Mořic Anger leading the National Theater Orchestra. It is scored for solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra shares the same title as its predecessor, and in certain respects, its model: Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra of 1944. Both works were the result of commissions from a conductor, and both make prominent use of folk idioms. Most notably, both works focus on sections of the orchestra, as well as solo instruments within the orchestra, as opposed to a concerto featuring one instrument placed in the forefront. Unlike Bartók, however, Lutosławski, while sincerely interested in exploring Polish folk music, did not continue to make this the touchstone of his mature style. Already during the long genesis of this work, he was beginning to explore more modernist compositional techniques, such as making use of twelve-tone serialism, that turned his style toward a different trajectory. His Concerto for Orchestra, therefore, while “modern” in many of its compositional elements, does not stray far from recognizable tonal and modal vocabularies, thus rendering it highly appealing to all audiences.

Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra is cast in three movements and lasts approximately 28-30 minutes. The first movement, Intrada: Allegro maestoso, begins violently with a series of ominous-sounding drumbeats that become the background pulse for the first theme—an idea derived from a folk melody of the region of Mazowsze, located in the mid-northeastern part of Poland. This idea is first articulated by the cello section and it eventually migrates its way throughout the rest of the orchestra. After another violent outburst, a more pastoral presentation of the principal theme brings the first movement to a gentle close.

The lively and shorter second movement, Capriccio notturno ed arioso: Vivace, is designed in a three-part form, with the arioso section functioning as the central part of a scherzo. The title implies a nocturnal atmosphere of a capricious nature. It opens softly in a light a feathery manner, and the influence of Bartók’s “night music” is discernable. The strings and winds scurry about playfully, leading to the arioso section, in which the trumpets declare a bold folk-like tune that is passed around the orchestra in skillful counterpoint. The return of the Capriccio is more spectral than it was in its initial hearing, punctuated by pizzicato strings and evocative percussion strokes, all within a hushed dynamic range.

The final movement is marked Passacaglia, Toccata e Corale: Andante con moto—Allegro giusto. The longest of the Concerto for Orchestra’s three movements, this finale begins with a passacaglia, a dance-variation piece with roots going back to the early 1600s. Works with this title are based upon a repeated melody, usually in the lowest pitched instruments (think of the popular Pachelbel Canon and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue for Organ). Lutosławski, like Bach, allows his eight-measure theme to migrate upwards during its eighteen variations, as well as presenting it in varying speeds. It begins softly with pizzicato basses and harp, building in intensity as it moves along, with very rapid activity throughout the orchestra. As the passacaglia segment comes to its conclusion, the theme is placed in the violin’s highest register. The word toccata, whose origins also lies in the late-Renaissance/early Baroque era, often refers to a kind of work for keyboard that exercises the performer’s dexterity. Lutosławski challenges all sections of the orchestra with spitfire passages of demanding virtuosity. Eventually this abates, creating space for the gentler chorale melody makes its entry. Once again the pace picks up, becoming ever faster and more energetic. Towards the end, the chorale makes a final appearance, accompanied now by a whirlwind of activity and leading to a thrilling climax.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2022